Archer

··Omega Qualified WatchmakerI admit this thread/task might not be as basic as some of the other watchmaking tips I’ve posted in these other threads:

https://omegaforums.net/threads/basic-watchmaking-tips-cleaning.56365/#post-696021

https://omegaforums.net/threads/basic-watchmaking-tips-oiling-part-1.62310/

https://omegaforums.net/threads/basic-watchmaking-tips-oiling-part-2-the-mainspring-barrel.71246/

https://omegaforums.net/threads/basic-watchmaking-tips-oiling-part-3-the-wheel-train.84482/

https://omegaforums.net/threads/basic-watchmaking-tips-spotting-wear.81025

/https://omegaforums.net/threads/basic-watchmaking-tips-oiling-part-4-the-escapement.87072/

However I wanted to address one step in this process that is often cited by amateur watchmakers as the reason they can’t change a balance staff. To do that I might as well go through the entire process.

So first off why do we need to change a staff? Well the most obvious is a broken staff, or a bent staff, but those are actually not common on watches with shock protection on the balance, so that leaves us with a worn or rusty staff. In the example I’ll show you, it’s a worn staff in a Cal. 321 movement that I have in the shop for servicing that is in rough shape in several ways. Here is the “good” end of the balance staff:

And here is the end that has a clear groove worn in it:

This warrants a closer look, so I used my higher power microscope to take this photo again of the good end:

And the end with the groove in it:

Note that in addition to that groove, the very end of the staff at this end has been worn flat from running without lubrication, so this staff certainly needs to be replaced.

So first off there are different methods in how balance staffs are actually attached to the balance. For example some vintage American pocket watch makers used what are known as "friction fit" staffs, and as the description implies they are fitted by friction:

In this thread I will address the most common method of staff attachment - the riveted staff.

So the first step in replacing a balance staff is to mark the balance so that the balance spring and roller are placed back on in the same orientation. The next step is to remove the balance spring, so here I have set the balance on a piece of plastic that has a hole in it so the wheel can sit flush on the plastic, and I’ll use a pair of balance spring levers to get under the balance spring collet and lift the spring off the balance:

Now removed:

The next step is to remove the roller, and there are a few different tools that can be used for this, but a simple roller remover works for me:

The remover has an inclined surface that acts as a wedge as you slide the balance into the tool, and when you get it in as far as it will go, a very light squeeze of the handles together will pop the roller off:

Here is the roller:

Now we have a bare balance - this is the rivet side:

And this is the hub side:

Let’s take a closer look at both sides under the microscope - the rivet side:

A bit closer:

The hub side:

So one area of controversy in watchmaking is how to remove a staff like this one that is riveted in place. One school of thought is that the staff can be punched out by force, so striking the staff from the rivet side, which will break off the rivet and free the staff. Personally I’m not a big fan of this method no matter what tool you might use to accomplish it (Platax tool, Hoira tool, staking set, etc.) because even if the rivet breaks off cleanly, there will be an enlarged portion of the staff (bulge under the rivet) that is forced through the hole in the balance, and this will potentially enlarge the hole and make riveting a new staff on more difficult. Now there are plenty of watchmakers who swear by the “punching it out” method, but it’s not how I do it.

I was taught to cut the staff out using a lathe, and looking back I have some photos from a previous staff replacement already in my Photobucket account, so this shows the process of cutting the staff out. So here is the balance with the spring and roller removed, and in my lathe ready to cut the hub end of the staff:

Here the cutting is in progress, and for this work I use a hand held carbide graver:

By cutting from the hub side, when you remove the hub it allows you to pull the balance straight off the staff, not having the riveted side go through the hole in the balance at all. Here I have cut the hub off and you see a small ring of material that has been cut free (I recall in watchmaking school having to hand in that little ring, so it was something all the students had to be able to do):

And the staff removed from the wheel:

Now this method requires proficiency with the lathe, and it doesn’t come without risks. One slip of the graver and you could throw the balance out of true, gouge it up, or otherwise damage it. I don’t have any difficulties using the lathe to do this sort of work, but I often come across amateur watchmakers who don’t have a lathe, so how would they remove the staff other than punching it out? For the 321 balance I thought I would use a tried and true method of removing stuck steel parts - soaking it in alum:

NOTE - since alum is very good at dissolving carbon steels, you obviously can’t use this method on a balance that is made of steel or has steel as a part of the actual wheel portion. This method is only for balances made of materials like Glucydur (as in this case) or other non-ferrous materials that are not affected by alum.

So I mixed a heaping teaspoon of alum with some warm water:

Here is the small glass with the alum dissolved in the water on my bench - you want a saturated solution of alum, so dissolve as much in the water as it the water will take:

And I place the balance in the water, and wait for the alum to start working:

It doesn’t take long before I see a good stream of bubbles coming from the staff:

Now I’m not in a rush doing these jobs since I always have several watches in progress at the same time, so on this one I left it for several hours. It didn’t appear that much had happened, but when I removed the balance and checked how tight the staff was, it came right out:

Now one small drawback of this method is that the balance was a little discoloured at first:

So I did a little manual cleaning of it, then placed it in a jar of cleaning solution:

And dropped that in my ultrasonic tank for a while:

Once that had gone through a few cycles, I dried it off and then ran it through my regular cleaning machine in a small basket:

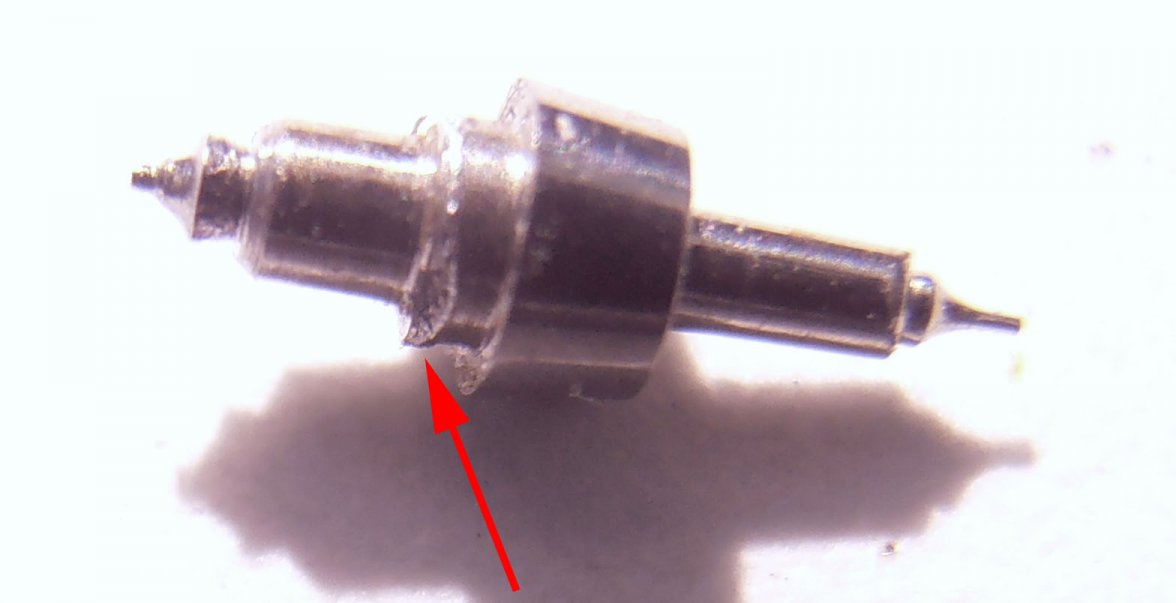

This is what the staff looked like by the way:

So here is a photo of the hole in the balance after it was cleaned, and you can see the hole is pristine and has no damage:

Here is the new staff:

Now it’s always a good idea to check the fit of the new staff before you rivet it to the balance, so here I have installed it in the movement, and I check things like end shake and side shake to make sure this is really the right staff:

I then test the fit of the staff in the balance - often with a balance that has had the staff punched out, the balance will essentially fall right on the staff, and in severe cases the hole will be significantly larger than the staff. This can lead to issue riveting the staff on, centering of the balance on the staff, etc. But in this case, I had to use a tiny bit of force to seat the staff into the balance, so the fit is very good:

This is what the rivet side of the staff looks like before it is riveted to the balance:

So next we want to rivet the staff to the balance, and to do that I use my staking set. I have a K&D “Inverto” staking set, which means all the punches (that come down from the top) can also be used as stumps on the bottom, and to me this is a must have in terms of staking sets as it provides you will endless options. This is important when staffing because you want to select punches that have very little clearance around the items you are using them on, so having more options will give you the best fit possible.

Here I have selected a punch to use as a base for riveting the staff, and I have placed the staff (rivet side up) in the punch:

Next I place the balance on the staff:

I start with a round nose punch, as I want to spread the rivet on the staff out first:

Lining the punch up exactly is critical, so you don’t damage the new staff:

You bring the punch down on the staff, and use your watchmaker’s hammer to tap the punch. It’s good practice to rotate the punch as you tap, as that will even out any errors in the event that your punch face it not perfectly flat to the base. Since these parts are all very small, you don’t have to hit hard, so really just letting the weight of the hammer fall on the punch:

I the switch to a flat faced punch, to fatten out the rivet a bit:

Same procedure...tap and rotate:

A look at the rivet, and it looks good:

But how do we know it is tight enough? There is a simple test - take a pin vise and secure the rivet side of the staff firmly in the vise, and place a very small rolled up “log” of Rodico putty on the opposite pivot. You then hold the balance with your fingers, and try to turn the staff with the pin vise - if the staff turns you will see it via the log of Rodico turning, and you need to go back and rivet the staff more. This one was fine - it didn’t budge:

The next step is to check and true the balance as needed, so I use the truing calipers for that. They have jewels on either end that the pivots of the staff fit into, and you spin the balance and use the gauge at the side to look for a wobble. Since we didn’t distort the wheel by punching the staff out, this one spins perfectly true so no adjustments required:

Note that one common side effect of having a hole in a balance that is too large is that due to the excess amount of riveting required to spread the rivet out to fill the hole, this can lead to the balance getting distorted in the flat or in the round. I’ve had to fight balances where the hole is oversized, and it almost always ends up in more work truing the balance after.

The next step is to install the roller, so again switching punches around to find a close fit, and then place the roller on the staff:

You bring the punch down on the roller, and you just press it on - no hitting with a hammer required!

So this is the stage where many books would tell you that you need to statically poise the balance. I’m going to give a brief review of that before I tell you why you probably shouldn’t do it. So you get out your poising tool, set it up directly on the solid wood surface of your bench, and place the bubble level on the ruby jaws of the tool:

You level the tool, and when done I use a pencil to mark where the feet of the tool were when level in case is moves. I also level the tool with my arms on the bench as if I was working, because if I level it with no load on the bench and then lean on the bench, it will go out of level. Once the tool is level, you place the balance on the tool, and I use a hair from a dial brush on a stick to move the balance and get it rolling:

The poising process is pretty simple - add or remove weight as needed so that the balance will not stop in any particular position, or swing like a pendulum. It should roll and stop in random positions, and then you have perfect static poise - great!

The problem is you likely just messed up the factory poise.

When a balance is poised statically, there are some obvious parts still missing from the assembly - collet, collet pin, balance spring, stud, and stud pin. So all this trouble perfectly poising the balance statically essentially goes out the window once you install the balance. When you mount it in the watch, and fix one end of the balance spring using the stud, now that adds other effects on the balance that make the poise act differently in use. There is a method of poising that accounts for all this called “dynamic poising” and it’s done using a timing machine and taking specific tests to determine where material must be added or removed from the balance. So for this watch I’m going to make an assumption that it was poised well as a system already, and I’m going to check the timing before I erase the factory poising.

One reason I can do this is that again I didn’t have any distortion in the balance wheel when riveting, because the staff fit the hole perfectly. If the hole was oversized, or I had to perform a lot of truing of the balance, then I would be more inclined to static poise the balance since I know the staffing operation has likely thrown everything out of whack anyway. So I would typically only static poise if I feel there is some sort of gross error that needs to be corrected.

So next I need to install the balance spring, and this requires a different thought process in the selection of the punch at the bottom - here is the balance showing the roller installed:

If I draw an imaginary circle want to select a punch as the base for this operation that has a hole in it that is just larger than the roller jewel, like so:

This will support the balance in a way that won’t cause any pressure or deflection on the arms or rim of the balance. So here I have that punch selected and installed in the staking set:

I place the balance spring on the balance:

One again no hammering, just pressing it on using my fingers on the punch:

The staff has now been changed:

From here I carry on with my normal servicing procedures, checking balance amplitudes, beat error, and of course positional variation:

So although this can be a daunting task for people the first time through, it’s actually a very straightforward task in many ways. I hope that with the use of alum it’s something that more people who are already working on watches may try, and of course if anyone has questions, please let me know.

Cheers, Al

https://omegaforums.net/threads/basic-watchmaking-tips-cleaning.56365/#post-696021

https://omegaforums.net/threads/basic-watchmaking-tips-oiling-part-1.62310/

https://omegaforums.net/threads/basic-watchmaking-tips-oiling-part-2-the-mainspring-barrel.71246/

https://omegaforums.net/threads/basic-watchmaking-tips-oiling-part-3-the-wheel-train.84482/

https://omegaforums.net/threads/basic-watchmaking-tips-spotting-wear.81025

/https://omegaforums.net/threads/basic-watchmaking-tips-oiling-part-4-the-escapement.87072/

However I wanted to address one step in this process that is often cited by amateur watchmakers as the reason they can’t change a balance staff. To do that I might as well go through the entire process.

So first off why do we need to change a staff? Well the most obvious is a broken staff, or a bent staff, but those are actually not common on watches with shock protection on the balance, so that leaves us with a worn or rusty staff. In the example I’ll show you, it’s a worn staff in a Cal. 321 movement that I have in the shop for servicing that is in rough shape in several ways. Here is the “good” end of the balance staff:

And here is the end that has a clear groove worn in it:

This warrants a closer look, so I used my higher power microscope to take this photo again of the good end:

And the end with the groove in it:

Note that in addition to that groove, the very end of the staff at this end has been worn flat from running without lubrication, so this staff certainly needs to be replaced.

So first off there are different methods in how balance staffs are actually attached to the balance. For example some vintage American pocket watch makers used what are known as "friction fit" staffs, and as the description implies they are fitted by friction:

In this thread I will address the most common method of staff attachment - the riveted staff.

So the first step in replacing a balance staff is to mark the balance so that the balance spring and roller are placed back on in the same orientation. The next step is to remove the balance spring, so here I have set the balance on a piece of plastic that has a hole in it so the wheel can sit flush on the plastic, and I’ll use a pair of balance spring levers to get under the balance spring collet and lift the spring off the balance:

Now removed:

The next step is to remove the roller, and there are a few different tools that can be used for this, but a simple roller remover works for me:

The remover has an inclined surface that acts as a wedge as you slide the balance into the tool, and when you get it in as far as it will go, a very light squeeze of the handles together will pop the roller off:

Here is the roller:

Now we have a bare balance - this is the rivet side:

And this is the hub side:

Let’s take a closer look at both sides under the microscope - the rivet side:

A bit closer:

The hub side:

So one area of controversy in watchmaking is how to remove a staff like this one that is riveted in place. One school of thought is that the staff can be punched out by force, so striking the staff from the rivet side, which will break off the rivet and free the staff. Personally I’m not a big fan of this method no matter what tool you might use to accomplish it (Platax tool, Hoira tool, staking set, etc.) because even if the rivet breaks off cleanly, there will be an enlarged portion of the staff (bulge under the rivet) that is forced through the hole in the balance, and this will potentially enlarge the hole and make riveting a new staff on more difficult. Now there are plenty of watchmakers who swear by the “punching it out” method, but it’s not how I do it.

I was taught to cut the staff out using a lathe, and looking back I have some photos from a previous staff replacement already in my Photobucket account, so this shows the process of cutting the staff out. So here is the balance with the spring and roller removed, and in my lathe ready to cut the hub end of the staff:

Here the cutting is in progress, and for this work I use a hand held carbide graver:

By cutting from the hub side, when you remove the hub it allows you to pull the balance straight off the staff, not having the riveted side go through the hole in the balance at all. Here I have cut the hub off and you see a small ring of material that has been cut free (I recall in watchmaking school having to hand in that little ring, so it was something all the students had to be able to do):

And the staff removed from the wheel:

Now this method requires proficiency with the lathe, and it doesn’t come without risks. One slip of the graver and you could throw the balance out of true, gouge it up, or otherwise damage it. I don’t have any difficulties using the lathe to do this sort of work, but I often come across amateur watchmakers who don’t have a lathe, so how would they remove the staff other than punching it out? For the 321 balance I thought I would use a tried and true method of removing stuck steel parts - soaking it in alum:

NOTE - since alum is very good at dissolving carbon steels, you obviously can’t use this method on a balance that is made of steel or has steel as a part of the actual wheel portion. This method is only for balances made of materials like Glucydur (as in this case) or other non-ferrous materials that are not affected by alum.

So I mixed a heaping teaspoon of alum with some warm water:

Here is the small glass with the alum dissolved in the water on my bench - you want a saturated solution of alum, so dissolve as much in the water as it the water will take:

And I place the balance in the water, and wait for the alum to start working:

It doesn’t take long before I see a good stream of bubbles coming from the staff:

Now I’m not in a rush doing these jobs since I always have several watches in progress at the same time, so on this one I left it for several hours. It didn’t appear that much had happened, but when I removed the balance and checked how tight the staff was, it came right out:

Now one small drawback of this method is that the balance was a little discoloured at first:

So I did a little manual cleaning of it, then placed it in a jar of cleaning solution:

And dropped that in my ultrasonic tank for a while:

Once that had gone through a few cycles, I dried it off and then ran it through my regular cleaning machine in a small basket:

This is what the staff looked like by the way:

So here is a photo of the hole in the balance after it was cleaned, and you can see the hole is pristine and has no damage:

Here is the new staff:

Now it’s always a good idea to check the fit of the new staff before you rivet it to the balance, so here I have installed it in the movement, and I check things like end shake and side shake to make sure this is really the right staff:

I then test the fit of the staff in the balance - often with a balance that has had the staff punched out, the balance will essentially fall right on the staff, and in severe cases the hole will be significantly larger than the staff. This can lead to issue riveting the staff on, centering of the balance on the staff, etc. But in this case, I had to use a tiny bit of force to seat the staff into the balance, so the fit is very good:

This is what the rivet side of the staff looks like before it is riveted to the balance:

So next we want to rivet the staff to the balance, and to do that I use my staking set. I have a K&D “Inverto” staking set, which means all the punches (that come down from the top) can also be used as stumps on the bottom, and to me this is a must have in terms of staking sets as it provides you will endless options. This is important when staffing because you want to select punches that have very little clearance around the items you are using them on, so having more options will give you the best fit possible.

Here I have selected a punch to use as a base for riveting the staff, and I have placed the staff (rivet side up) in the punch:

Next I place the balance on the staff:

I start with a round nose punch, as I want to spread the rivet on the staff out first:

Lining the punch up exactly is critical, so you don’t damage the new staff:

You bring the punch down on the staff, and use your watchmaker’s hammer to tap the punch. It’s good practice to rotate the punch as you tap, as that will even out any errors in the event that your punch face it not perfectly flat to the base. Since these parts are all very small, you don’t have to hit hard, so really just letting the weight of the hammer fall on the punch:

I the switch to a flat faced punch, to fatten out the rivet a bit:

Same procedure...tap and rotate:

A look at the rivet, and it looks good:

But how do we know it is tight enough? There is a simple test - take a pin vise and secure the rivet side of the staff firmly in the vise, and place a very small rolled up “log” of Rodico putty on the opposite pivot. You then hold the balance with your fingers, and try to turn the staff with the pin vise - if the staff turns you will see it via the log of Rodico turning, and you need to go back and rivet the staff more. This one was fine - it didn’t budge:

The next step is to check and true the balance as needed, so I use the truing calipers for that. They have jewels on either end that the pivots of the staff fit into, and you spin the balance and use the gauge at the side to look for a wobble. Since we didn’t distort the wheel by punching the staff out, this one spins perfectly true so no adjustments required:

Note that one common side effect of having a hole in a balance that is too large is that due to the excess amount of riveting required to spread the rivet out to fill the hole, this can lead to the balance getting distorted in the flat or in the round. I’ve had to fight balances where the hole is oversized, and it almost always ends up in more work truing the balance after.

The next step is to install the roller, so again switching punches around to find a close fit, and then place the roller on the staff:

You bring the punch down on the roller, and you just press it on - no hitting with a hammer required!

So this is the stage where many books would tell you that you need to statically poise the balance. I’m going to give a brief review of that before I tell you why you probably shouldn’t do it. So you get out your poising tool, set it up directly on the solid wood surface of your bench, and place the bubble level on the ruby jaws of the tool:

You level the tool, and when done I use a pencil to mark where the feet of the tool were when level in case is moves. I also level the tool with my arms on the bench as if I was working, because if I level it with no load on the bench and then lean on the bench, it will go out of level. Once the tool is level, you place the balance on the tool, and I use a hair from a dial brush on a stick to move the balance and get it rolling:

The poising process is pretty simple - add or remove weight as needed so that the balance will not stop in any particular position, or swing like a pendulum. It should roll and stop in random positions, and then you have perfect static poise - great!

The problem is you likely just messed up the factory poise.

When a balance is poised statically, there are some obvious parts still missing from the assembly - collet, collet pin, balance spring, stud, and stud pin. So all this trouble perfectly poising the balance statically essentially goes out the window once you install the balance. When you mount it in the watch, and fix one end of the balance spring using the stud, now that adds other effects on the balance that make the poise act differently in use. There is a method of poising that accounts for all this called “dynamic poising” and it’s done using a timing machine and taking specific tests to determine where material must be added or removed from the balance. So for this watch I’m going to make an assumption that it was poised well as a system already, and I’m going to check the timing before I erase the factory poising.

One reason I can do this is that again I didn’t have any distortion in the balance wheel when riveting, because the staff fit the hole perfectly. If the hole was oversized, or I had to perform a lot of truing of the balance, then I would be more inclined to static poise the balance since I know the staffing operation has likely thrown everything out of whack anyway. So I would typically only static poise if I feel there is some sort of gross error that needs to be corrected.

So next I need to install the balance spring, and this requires a different thought process in the selection of the punch at the bottom - here is the balance showing the roller installed:

If I draw an imaginary circle want to select a punch as the base for this operation that has a hole in it that is just larger than the roller jewel, like so:

This will support the balance in a way that won’t cause any pressure or deflection on the arms or rim of the balance. So here I have that punch selected and installed in the staking set:

I place the balance spring on the balance:

One again no hammering, just pressing it on using my fingers on the punch:

The staff has now been changed:

From here I carry on with my normal servicing procedures, checking balance amplitudes, beat error, and of course positional variation:

So although this can be a daunting task for people the first time through, it’s actually a very straightforward task in many ways. I hope that with the use of alum it’s something that more people who are already working on watches may try, and of course if anyone has questions, please let me know.

Cheers, Al